3 What it takes to optimize soil health and water management in Africa

3.1 Requirements for optimizing sustainable soil and water management

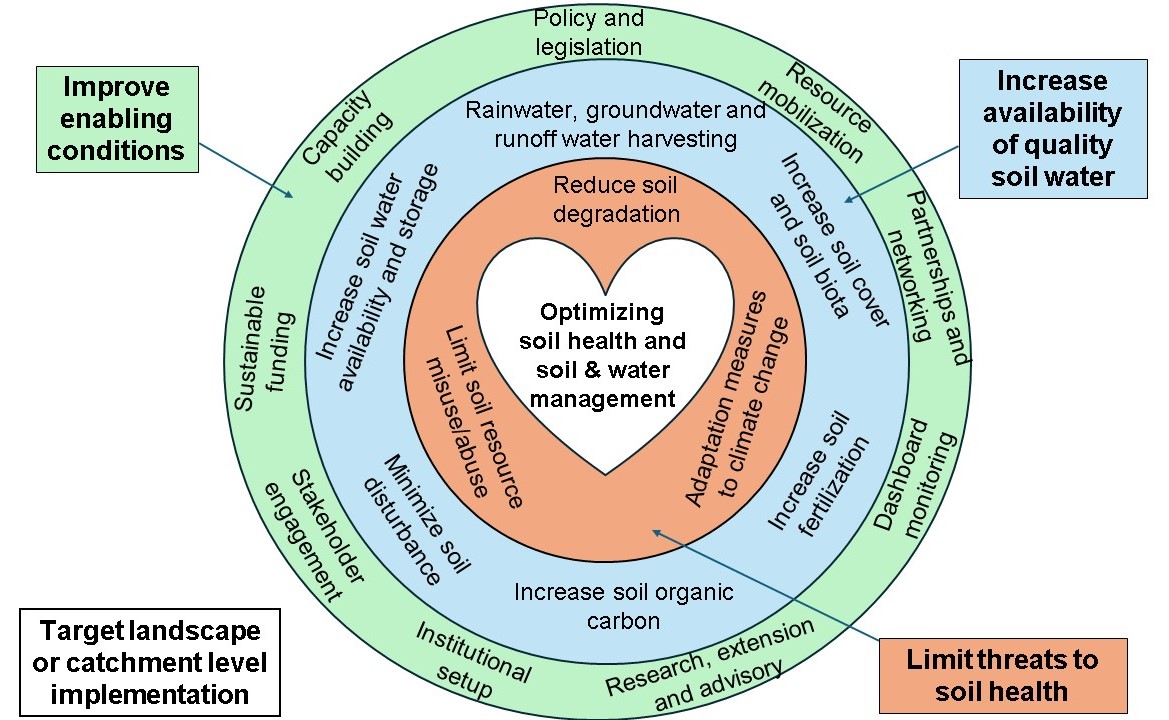

Optimizing soil health and soil water management entails minimizing threats to soil health while increasing or maintaining the availability of good quality soil water. Therefore, soil health and soil water management options to consider in the optimization are those that focus on attaining maximum desired conditions for soil health and soil water while limiting the advancement and/or impacts of threats to soil health (Figure 3.1).

Figure 3.1: Important considerations for optimizing soil health and water management

3.1.1 Control threats to soil health

Reduced or minimal threats to soil health are the most important requirement for optimizing soil health and water management. Soil threats negatively impact soil health and the availability of quality soil water. Therefore, it is essential to focus on reducing the threats to achieving optimal soil health. Threats to soil health are controlled by reducing soil degradation (such as through proper soil and water conservation measures, (Mahajan et al. 2021)), limiting soil misuse/abuse (e.g., through awareness creation and community mobilization against misuse and abuse of the soil resource, Drechsel et al. (2001)), and building adaptation measures against effects of climate change (such as through conservation agriculture practices, Rattan Lal (2012)).

Soil degradation is the major reason soil health is declining worldwide. In Africa, soil degradation is approximated to affect more than 65% of the continent and this is increasing the negative impacts of climate change. Soil degradation, together with nutrient depletion, is also touted as the primary enemies of Africa’s sustainable agricultural productivity (Dimkpa et al. 2023; AU-FARA 2024; R. Lal and Stewart 2019). Therefore, limiting soil degradation and soil threats in general should be a priority requirement for improving soil health in Africa. In Figure 3.1, controlled soil threats are prioritized by putting them in the innermost circle close to the heart of soil health and water management.

3.1.2 Increasing availability of quality soil water

Increasing the availability of quality soil water ensures adequate exchange of nutrients between soil and plant roots, facilitates the supply of water needed by soil biota, regulates the exchange of water between soil and the environment, and provides a cooling effect in the soil, among other functions. Water is also important in soil health because, being a universal solvent, it can dissolve and influence the characteristics of pollutants and contaminants in the soil. In the drylands where water is an important limiting factor for plant growth, soil water plays a crucial role in shaping overall soil health. Therefore, increasing the availability of quality soil water is very important in optimizing soil health and water management. In Figure 3.1, it is included in the second tier of important considerations for promoting soil health and water management.

Strategies for increasing quality soil water include (Ali et al. 2018; Shaxson and Barber 2003):

- Increasing soil water infiltration and storage through techniques such as irrigation, drainage, sub-surface water storage (e.g., deep tillage), careful use of soil amendments, etc.

- Increasing soil organic carbon through organic manuring, residue incorporation, etc.

- Minimizing soil disturbance such as in conservation agriculture

- Increasing soil cover through agroforestry, cover cropping, mulching, etc.

- Increasing soil fertilization through integrated soil fertility management

- Harvesting water from rainwater, runoff, and groundwater resources

3.1.3 Targeting landscape or watershed level implementation of soil and water conservation measures

Landscape or watershed level soil conservation is important because it integrates conservation plans with other societal plans which address issues affecting communities, such as climate change, water resources management, etc. Targeting landscape level implementation of soil and water conservation measures is also important because most threats to soil health depend on processes that occur at landscape or watershed scales. Furthermore, focusing on watershed or landscape scale can bring different stakeholders and many landowners/farmers together and improve group discussions and knowledge sharing, which is more inclusive and successful than disjointed attempts at many local or plot levels. There are also studies which show that soil and water conservation measures at the landscape scale are more effective in controlling soil degradation than at the local or plot scale (Wickama, Masselink, and Sterk 2015). Therefore, targeting the implementation of soil conservation measures at the landscape level should be a prerequisite for effective optimization of soil health and water management.

Effective implementation of landscape level planning for soil and water management requires the following factors to be considered:

- Identification of degradation hotspots and extent of degradation

- Factors influencing degradation and their distribution on the landscape

- Options for soil and water conservation measures for different target area

- An enabling institutional arrangement

- Available stakeholders and partner

3.1.4 Improving enabling conditions

Enabling conditions are the social, policy, legal, institutional, technical, and financial contexts which can influence the implementation of soil and water management. Improving enabling conditions aims to promote the influential factors to favor the establishment and sustainability of soil and water conservation measures. It includes:

- Improving and implementing relevant policies and legislation

- Supporting relevant government departments to oversee technical guidance, supervision, and enforcement of regulations and standards

- Developing relevant information systems and monitoring dashboard for sharing progress on the status of soil health

- Promoting the framework for stakeholder engagement, collaborations, and for forging partnership and networking

- Assessing and encouraging mechanisms and collaborations for resources mobilization, budgetary allocations, and farmer investments in establishment and maintenance of soil and water conservation measures

- Promoting cutting-edge research and development of efficient technology and monitoring systems for soil water management

- Supporting capacity-building through farmer field schools in model farms or living labs, extension, and advisory services

3.2 Implementation challenges for sustainable soil and water management in Africa

3.2.1 Poorly planned conservation measures

Poorly planned conservation measures are difficult to implement and maintain during their lifespan. They are often not properly matched with the soil degradation they are supposed to control, improperly placed in the landscape, have poor technical designs, and may not be suitable for the ecological conditions where they have been implemented. Poorly designed conservation measures may lead to degradation due to the impacts of their negative influence. Some of the features of poorly planned conservation measures are:

- Inadequate number and spacing of the conservation measures in the target area

- Inadequate consideration of the influential factors during the planning and implementation of the conservation measures

- Focusing on plot-scale instead of landscape scale for processes that occur at the landscape scale

- Inappropriate conservation measures for the target soil threat to be addressed

- Incomplete implementation or technical design of the conservation measures concerned

- Top-down approach without the involvement of the local communities during planning and implementation of the conservation measures

3.2.2 Stakeholder behavior and changing land uses

Stakeholders in soil conservation are landowners, local users of natural resources, and government representatives. Others are agro-input dealers, scientists, NGOs, and organizations of agri-food industries and consumers. The active involvement of stakeholders in planning, implementation and maintenance of soil conservation measures has a bearing on the success of the soil conservation efforts (Wang and Aenis 2019). This implies implementation challenges when stakeholders withdraw their participation or change their interest midstream of the soil conservation projects. Stakeholders can change their interest or withdraw their support because of leadership or coordination changes, poor coordination and incentives, changes in regulations and priorities, changes in funding mechanisms, wrangles and infighting, competing interests, changes in land use, and impacts of natural disasters, etc.(Mekuria et al. 2021). Other forms of stakeholder behavior that can bring implementation challenges include resistance to change, sneaking in old habits into new technologies, and insubordination (Aghabeygi et al. 2024).

Implementation challenges may also be experienced when land use changes in the target area, which can alter the factors driving soil degradation, the stakeholders’ priority focus, the availability of funds and technical staff to implement or carry out maintenance, etc. Apart from land use changes, changes in land sizes can also influence the effectiveness of some soil and water conservation measures.

3.2.3 Inadequate maintenance and monitoring

Some soil conservation measures require regular maintenance to function effectively throughout their lifespan. Poorly maintained conservation measures can lead to soil degradation, promote the growth of pests and diseases, encourage unwanted plants and consequent competition for nutrients and water with crops, etc. Poor maintenance of conservation measures may arise due to a lack of technical knowledge, inadequate resources for maintenance, inadequate or incomplete design, changes in ownership, socio-economic factors (e.g., conflicts, political influence, changing demography of active workforce, etc.), abandonment, aging conservation measures that are cumbersome and expensive to maintain, etc.

Lack of proper monitoring can also affect maintenance and timely management of soil conservation measures. Monitoring provides requisite information that can be used to maintain, improve, or change the design of soil conservation measures.

3.2.4 Inadequate financial sustainability

Most sustainable soil and water conservation measures promoting soil health require sustained financial support to cater for the cost of installation, maintenance, improvements and adjustments, extension services, and labor requirements. Lack of or insufficient funding can starve the operationalization of soil conservation efforts. In Africa, most funding of soil conservation projects comes from governments, development partners (donors, NGOs, well-wishers, loans or grants from financial institutions, etc.), local communities, and landowners/farmers. The motivation to invest in soil and water conservation measures often comes from global/continental initiatives, governments, environmentalists, scientific research, incentives from the business community, public demand, especially where degradation is viewed as threatening public lives or livelihoods, and from farmers’/landowners’ own initiatives (such as to reduce loss of land to erosion, increase yields, produce quality agri-products, etc.). Inadequate or lack of proper motivation can trigger insufficient investment in soil and water conservation projects and consequently hinder conservation efforts (Aghabeygi et al. 2024).

Inadequate funding or investment in soil and water conservation projects may be due to:

- Low level of prioritization of soil conservation and soil health

- Lack of awareness and knowledge of the importance of soil health and soil conservation

- Low confidence in the ability for proper management of financial resources

- Poor publicity and communication with funding organizations

- Shrinkage of economic performance from sources of funding

3.2.5 Inadequate institutional support

Inadequate institutional support encompasses insufficient or lack of adequate social, policy, legal, and technical support in the implementation of soil and water conservation projects. Inadequate support may fail to enjoin stakeholders, fail to cover implementation activities legally, lack regulatory mandate to guide and standardize soil and water conservation measures, or lack motivation to promote conservation activities.

Inadequate policy and legal support may be in the form of:

- Inconsistent or lack of proper policies and laws for soil protection

- Lack of adequate policies, laws and detailed regulations for protecting the destruction of natural resources, dealing with encroachments, and for committing landowners or users to install soil conservation measures on their property

- Inadequate enforcement of existing policies, laws and detailed regulations regarding soil conservation measures

Inadequate social institutions are in the form of:

- Lack of properly constituted community organizations to champion soil and water conservation efforts

- Social organizations without a clear vision for soil conservation

- Improperly motivated social groups who are not pulling together to drive soil and water conservation activities in the target areas

Inadequate technical government departments to support conservation may be in the form of:

- Understaffed technical government departments

- Underfunded technical government departments and inadequate facilitation of core activities in soil conservation projects

- Lack of coordination and leadership among relevant institutions

- Unclear mandate of institutions involved in various aspects of soil and water conservation

- Lack of expertise in technical areas of soil and water conservation

- Weak enforcement of regulations and standards

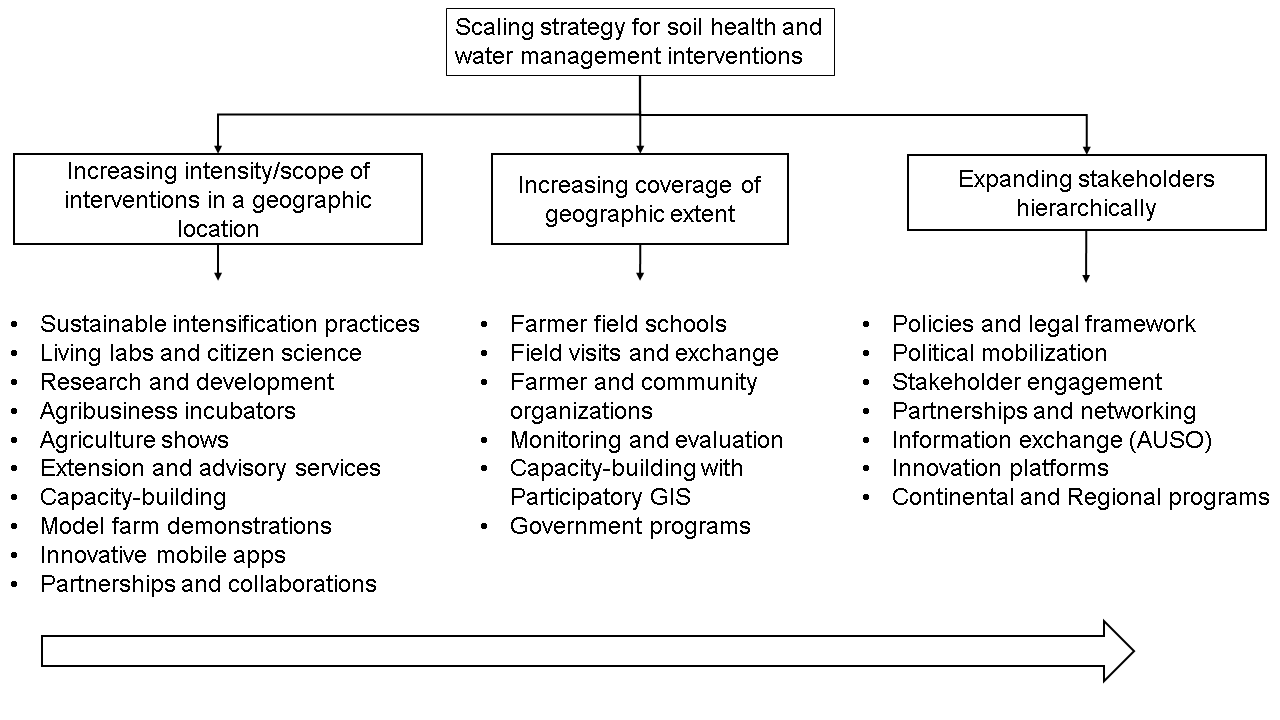

3.3 Strategies for scaling soil health and water management

Scaling soil health and water management can take different dimensions. For example, there is a scaling dimension involving the replication of successful conservation interventions to similar ecological settings in different geographic extents/boundaries (Ajayi, Oluwole, and Akinbamijo 2022). A second scaling dimension involves an increase in the intensity of activities in a geographic boundary due to innovations or improvements of the existing interventions. In addition, the third scaling dimension involves the incorporation of more stakeholders hierarchically from the local level to communities, national governments, up to the continental or global levels (Ajayi, Oluwole, and Akinbamijo 2022).

Various strategies can be employed to scale soil health and water management depending on the target scaling dimensions (Figure 3.2).

Figure 3.2: Strategy for scaling soil health and water management interventions in Africa

3.3.1 Strategy for increasing scope in a geographic location (deep scaling)

Implementation of soil and water conservation measures may sometimes attract innovations and improvements that give more success and scope. For example, the use of superabsorbent polymers to increase water retention in combination with traditional runoff water harvesting and cover crops is an interesting innovation that may be more effective in soil water management in drylands (Yang et al. 2022). Similarly, combining the push-pull system of mixed cropping with fodder crops (such as Brachiaria, Desmodium, etc.) can expand the scope of soil conservation to include pest and disease control and the provision of animal feeds. Such innovations can scale the scope of soil and water conservation at the plot/farm level, which may be beneficial for soil health improvement.

The strategy for scaling the scope and intensity of soil and water conservation is to develop guidelines to test, validate, and promote innovations using research for development, living labs, show-casing model farms, extension services, agribusiness incubators, etc. (Figure 3.2). Innovative mobile apps, publications (such as farmer-centered periodicals, journals, newsletters, etc.), dedicated promotional websites, shows, conferences, and webinars are examples of programs that can be used to promote the scaling of innovations.

3.3.2 Strategy for covering wider geographic extents (horizontal scaling)

Expanding the areas under successful soil and water conservation measures is the antidote for widespread soil degradation in Africa, estimated to affect more than 65% of the continent. Scaling into wider geographic extents will ensure that many African areas will eventually be covered with successful soil and water conservation measures. Currently, the total coverage of soil and water conservation measures is not clearly known in Africa, particularly in the croplands, grazing land (grasslands), and forested areas.

The strategy for scaling geographic coverage will target expanding successful soil and water conservation measures for croplands, grazing land (grasslands), and forested areas with similar ecological conditions. The strategy will involve developing scaling toolkits for farmer field schools, field visits and exchange programs, customizable capacity-building curricula that include community participatory GIS, monitoring and evaluation, etc. (Figure 3.2). The strategy should be discussed with relevant national government departments for incorporation into their plans and agenda.

3.3.3 Strategy for hierarchically incorporating more stakeholders (vertical scaling)

Stakeholders are the engine for driving the implementation of soil health and water management interventions. Their involvement can also be scaled accordingly to further catalyze the implementation of conservation interventions. The scaling may entail incorporating higher-level stakeholders such as the national government (for aligning soil conservation and soil health into national development plans and budgetary allocations), regional bodies (such as regional economic blocks (RECs) to foster transboundary conservation efforts), and continental initiatives and programs. Hierarchical scaling also ensures vertical communication and coordination that is necessary for harmonized conservation efforts and equitable enabling environments in different parts of Africa.

Strategies for vertical scaling include increasing the participation of various stakeholders such as local NGOs, government departments, development partners, regional economic blocks (RECs), and continental organizations such as AU, AUC, FARA, etc. (Figure 3.2).